I remember driving up to a practically empty piece of waste ground, walking through a rusty fence, which did little to keep anything in or out, and my father being stopped by the ticket man, who didn’t offer us a ticket. I’m sure a lot of haggling went on, but eventually we were shown two ponies and the five of us (my parents; my sister, aged six; and my brother, aged four) trotted down the Siq, over a very rocky path, right to the Treasury entrance. I remember worrying about the ponies’ ankles and flinching when they were whipped.

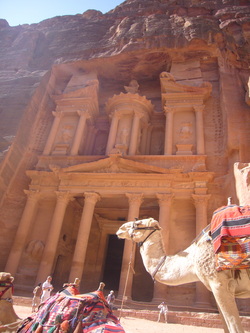

The Treasury was an impressive sight even to my young eyes, beautiful in rose sandstone. I remember seeing Bedouins living in the tombs carved into the rock face, and young boys harassing my father to give them his pen. Not understanding the material desire of people who have nothing, I was upset that my father was being asked to give something away under duress.

Thirty years on, I had a conversation with one of the hotel staff and recounted the story of the pen. He laughed and kindly put everything in perspective. Thirty years ago there were only pencils in Jordan. Pens were so rare they were a desired status symbol. It was not a charming attempt to mug my father, but in the Bedouin spirit, they were offering him the chance to show his generosity. There is no need even to say thank you to the giver. The act of giving is something that is marveled and develops a man’s reputation and community standing.

Petra itself has not changed. The narrow Siq walls still form a dark veil from the visitors’ first glimpse of the Treasury. Rock endures more than three decades of visitors. The sheer size of the site is staggering, and the resourcefulness of the local tribes inspiring. How do you carve such beautiful statues out of the face of a rock? And then how do you burrow into the mountain itself and create chambers that dwarf today’s mansions? My only thought is that religious belief sustains man in his endeavours. I can say this with little understanding - I observe and respect all religious beliefs, observe being the operative word. If man needs to create shelter for his family, surely he creates something basic but practical. There is no need for two storey, awe-inspiring grandness when the work is arduous, dangerous and painfully slow.

I’d like to say the place is timeless, but there are changes, and not all good. For the protection of the site no-one lives in the ruins anymore. A new village was created above Wadi Musa where damp, dark caves were exchanged for modern prefabs with windows and electricity. With the number of visitors you can no longer travel by horse right the way through the Siq unless you pay for a carriage. And the boulders underfoot have been replaced by a neat concrete path.

But it is the question of money that frightens me most about this place. It has to be the most expensive tourist attraction I have ever been to, particularly as it’s in a developing country. Don’t get me wrong. I studied history at university and I’m intrigued by the past, and long to protect it from the wake of unthinking development. People should be allowed to visit in order to understand how the world has changed, how all the jigsaw pieces fit together. And if there is a choice between building discrete tourist facilities or letting people pee in the tombs, I’m for the former even if it does slightly detract from the aesthetic look. The aim should surely be about giving access, but within certain boundaries.

I support entrance fees where profits are ploughed back into projects to aid further historical research or protection. But I’m not in favour of extortion, where it is difficult to see where the profits lie. Petra is an example. Without exception a tourist has to pay JD50 (GBP50) to enter the site. This includes an 800m horseride to the entrance of the Siq (but the money doesn’t go to the horseman who depends on tips). The entrance fee also includes a guide (who was nowhere to be seen.) Additionally you are welcome to pay for your own private guide, and hire a carriage when you’re tired.

As money transfers hands in a cash form only, we were practically wiped out. And I just don’t know where the money goes. The visitor centre was still under development, although there was little evidence of work, and our 2009 guidebook suggested a completion date of 2011. It was a relief to find that there were toilet facilities, but they were filthy, often with broken taps. There were hawkers everywhere and untidy little makeshift shops. I’m all for entrepreneurial spirit, but in all fairness, this was simply about ripping off unsuspecting tourists, who at the end of the day had little cash, or desire, to buy extras after the extortionate entrance fee, meaning that those who could really have benefitted from an extra dinar were ignored. As I say, it seems unfair and not really in the true spirit of archeological preservation or exploration.

I’m hoping these sour memories will fade and not become another pen story to niggle me for the next 30 years. It really is an amazing place and the climb over to the High Place of Sacrifice and over the other side to the Qasr al-Bint was well worth it, even with a five and three year old in tow. Despite the six mile hilly route they climbed like little soldiers, bribed onwards by the promise of a snack.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed